Category Archives: General

Leave a reply

eBPF and XDP Stuff

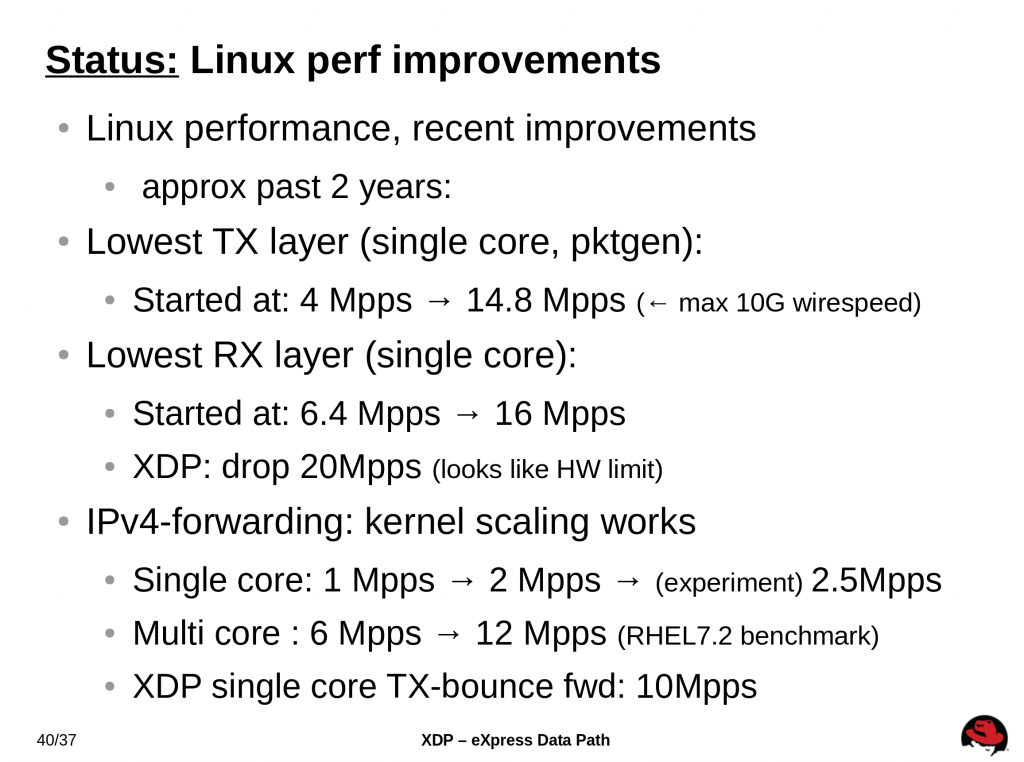

Worked example of DDOS protection using XDP. It also has this interesting slide:

eBPF Longest Prefix Match Maps

Coming soon to a 4.11 kernel near you, eBPF maps that can do longest prefix matches for things like IP routing.

Awesome.

XDP

There is a lot happening on the XDP front in the Linux kernel these days. This presentation provides a good overview.

I love the idea that eBPF is becoming a policy language for the kernel.